Surfacing the hidden curriculum: Learning the rules of academic writing

It is said that knowledge is power. This is because with knowledge, and in particular with education, comes opportunities and a greater chance of embracing your life’s potential. But how can knowledge become power for those who don’t yet possess either of these things? How do we create social justice through education for students who come from many different backgrounds?

In part two of the webinar ‘Surfacing the hidden curriculum: Levelling the playing field for students’, Richard Ingold looks at how knowledge of language and writing conventions can impact students’ chances of success and provides practical advice on supporting student writers.

You can watch the Play Again here. Keep reading for a summary of the key ideas.

There are rules to successful writing. It doesn’t matter whether it’s a poem, a business email or even (if you’re a little old-fashioned like me) a postcard, there are certain reader expectations you have to conform to if you’re going to get your message across effectively. And when it comes to academic writing, knowing these rules is what will get you high marks.

Basil Bernstein (2000) and Ruqaiya Hasan (2009) looked into how these rules are learned and discovered that family background plays a key role. If you’ve been brought up around literature, reading and a wide variety of texts, you have a distinct advantage when it comes to understanding and producing high-status written language – you’re going to know intuitively what it takes to be successful. However, if you’re from a low socioeconomic background, and so may not have had access to lots of different types of writing, or are from a different culture, whose writing rules are probably different, straightaway you’re disadvantaged.

So how can we help students from these backgrounds do well?

Visible pedagogy and social justice

According to Rose and Martin (2012), a teacher should have “a strong focus on the explicit transmission of knowledge about language with the aim of empowering otherwise disenfranchised groups”. For teachers, especially in higher education and English language teaching, the aim should be to help students successfully produce the written texts they need in their daily, professional and academic lives through the explicit transmission of knowledge about writing – we have to be clear about what we want them to do, and we need to set out plainly the rules of the game.

Meaning packed language

Of course, many teachers have been lucky enough to grow up around literature and high-status writing, and so we write and recognise good writing by instinct. The problem this causes is that, to be effective teachers, we then need to consciously examine the rules which we intuitively know. Luckily, by drawing on both Legitimation Code Theory (LCT) and Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL), we have the tools to uncover and teach ‘the tricks of the trade’ which successful writers use.

A key concept here is Semantics. In LCT, Semantics looks at how much meaning is packed into a symbol or word. A Remembrance Day poppy, for example, is on one level a simple plastic flower. Yet it is also semantically dense, crammed with meaning and symbolism. The same thing is true with language. For art students, ‘painting’ is a less semantically dense word than ‘cubism’, for example. Semantics is also concerned with how context dependent a meaning is. Consider the examples below, in which the more meaning there is in the words themselves, the less reliant on the context a listener or reader needs to be for understanding.

It’s not just the words you use, but how you use them: introducing semantic waves

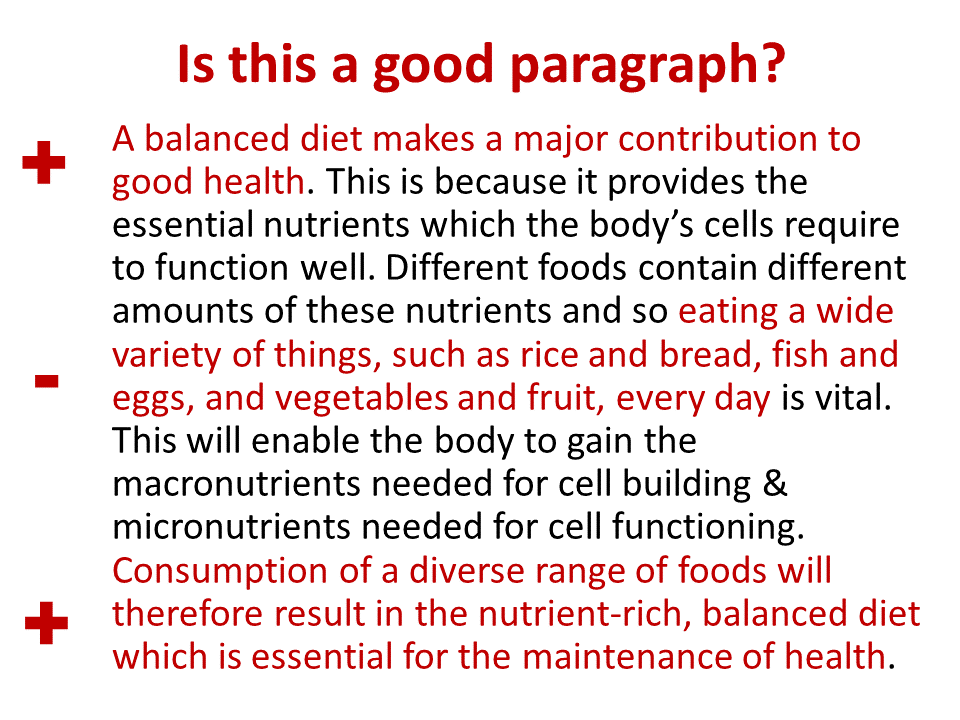

So using meaning-packed language is what academic writing is all about, isn’t it? Well, what LCT has revealed (Martin & Maton, 2013; Maton, Hood & Shay, 2016) is that in a paragraph, if you only use this kind of language, you will end up with unsupported ideas and a poorly written paragraph. This is often a trap for students who may have the misguided belief that using lots of big words is the only way to get the high marks. In contrast, if they use nothing but everyday language, they will also end up with low marks as they can only express concrete ideas and not the big, generalised concepts needed for academic enquiry.

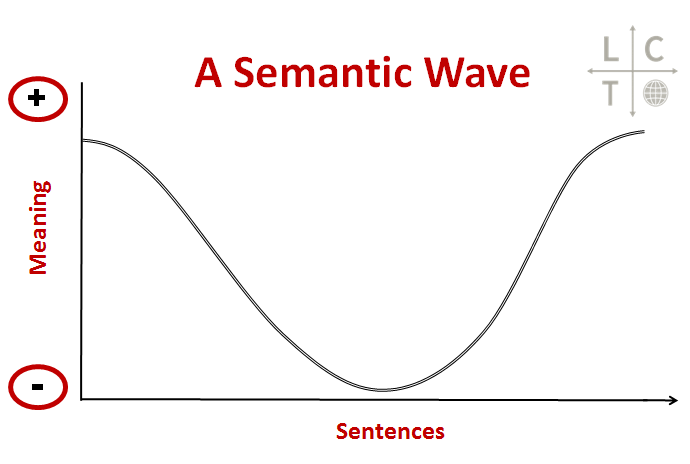

The key to success is being able to move between meaning-packed language and everyday language. Students have to be able to express theories and make generalisations about the world, and then ground these in the real world using everyday language. They also have to pull back up into theory to show they understand the implications of the examples they have used. It is this shift in language and ideas which is highly valued in good academic writing and, incidentally, is an important way students can demonstrate critical thinking. And it is this shift which creates the ‘semantic wave’.

Consider the example paragraph below, which I use with my lower-level academic classes. It shows how the semantic wave can be put into practice and how inseparable language and ideas are. NB: Meaning-packed language is identified with a ‘+’ and everyday language is identified with a ‘-’.

Not just for English teachers

The great thing about introducing the wave to students is that it gives them an easy-to-remember visual resource, a tool to help them link theory with concrete examples and, importantly, a way to think about the words they are using to express their ideas. And you don’t have to be an English language specialist to embrace it in your teaching as all you’re really doing is showing students where and how to introduce their key ideas, and where and how to explain and exemplify them. The lucky ones, who can already write well, will be fascinated to see the mechanics of what they intuitively know, while the students who lack that intuition will be shown one of the most important secrets of academic success.

Watch the Play Again for resource ideas. To continue the conversation, contact Richard Ingold, or share your thoughts and ideas about ways to support academic writing via Yammer, Twitter and/or LinkedIn with the hashtag #ELT.

References

- Bernstein, B. (2000). Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity: theory, research and critique (Revised ed.). Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Hasan, R. (2009). Semantic variation: meaning in society and in sociolinguistics. London: Equinox.

- Martin, J. R. & Maton, K. (Eds.). (2013). Cumulative knowledge-building in secondary schooling. Linguistics and Education, 24(1), 1-74.

- Maton, K., Hood, S. & Shay, S. (Eds.). (2016). Knowledge-building: educational studies in Legitimation Code Theory. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

- Rose, D. & Martin, J. R. (2012). Learning to write, reading to learn: genre, knowledge and pedagogy in the Sydney school. Sheffield (UK) and Bristol (USA): Equinox Publishing Ltd.